Episode Transcript

*This transcript was compiled using automated software — spelling and punctuation errors are possible.

Jason: Good afternoon. Today we are joined by Mark Jenkins, the founder and Executive Director of the Connecticut Harm Reduction Alliance, based in Hartford, Connecticut. Mark is going to share with us today his journey having started the Harm Reduction Alliance many years ago. Where they started, the path they’ve taken, where they are today and hope to be in the future.

Mark – welcome, it’s great to have you, always a pleasure.

Mark: Thank you, Jason. Glad to be here.

Jason: We’ve worked together for a couple of years now, but could you share with the audience what the Connecticut Harm Reduction Alliance does? What’s your mission and your current goals and objectives?

Mark: The Connecticut Harm Reduction Alliance, formally the Greater Hartford Harm Reduction Coalition, is a harm reduction organization. It is the only harm reduction organization in Connecticut by mission, vision, and value, meaning that we encompass harm reduction best principles entirely. That’s the only thing we do. Harm reduction is not a sub-mission of our organization, it is what we eat, sleep, and drink.

The goal is to help individuals reduce the amount of harm caused as a result of their actions, whether that be around illicit substance use, commercial sex work, homelessness, etc. We do this through advocacy, education, information, and offering of equipment such as syringes or safe sex supplies. We also provide some case management around housing and have evolved to encompass a medical model as well where we have vaccine storage with two nurses on duty to administer.

Join the thousands of responders using Beacon worldwide.

The organization has grown over the years from the back seat of my GMC Safari. I had to chuckle this morning when I saw an old grant application that showed we had one full time staff member. Thinking back on those earliest days, we had me, an administrative assistant, and maybe 15 volunteers, and at that point I think we did somewhere around 57,000 syringes annually and might have made around $63,000 for income that year.

Fast forward to now and we’ve amassed a two-story former law office, two other brick and mortar locations here in Hartford, an RV, fleet of five minivans and 30 staff members. We’re doing about 70,000 syringes a month, we do anywhere between 10 to 25 overdose calls a month, and are the state’s largest hand to hand distributor of Naloxone in addition to fentanyl test strips and full drug checking.

We are in the field 14 hours a day, consistently. That’ll be increasing to 17 hours a day when we’ve got our new outreach team in place. So Monday through Friday, 17 hours a day, we’ve got people in the field trying to provide services in one form or another.

So the organization has taken off. We support approximately 40% of the state via our services. But you know, it’s always a work in progress.

Jason: It’s quite an impressive work in progress, I mean, that’s a huge accomplishment in all these different areas. Could you share how it all got started. You’re the founder, you mentioned you started with just that administrative assistant. What led you to start a harm reduction organization, particularly at a time when harm reduction, to say the least, wasn’t widely accepted at all?

Mark: Frustration, ignorance, passion… and I don’t know which order those came in but I think ignorance might have led the way. I had no idea what I was getting myself into but I had worked for a couple organizations over the years doing outreach to marginalized populations, which was a changing industry, and I felt more could be being done in various neighborhoods to have more of an impact. My pleas to do more always fell on deaf ears, and at the time the organization I worked for didn’t seem to always have my community’s best interest at heart. And when I say my community’s best interest, that’s the people who live on the streets that I serve.

I felt like I could do a better job, so I tried myself. Unfortunately, I did not have an idea just what it would take to launch this effort, but that’s where the passion and my belief system came in that we could do this and that’s what kept me at it for five years without a paycheck.

Jason: What were the first steps you took when you set up?

Mark: I put it on Facebook, which committed me. Once I put it on Facebook I was saying out loud, “Who better to do this work? This is what I am, this is who I am.”

I’m a harm reductionist you know, and who better to serve my community than someone who is in the community who has a vested interest in the community.

I believe from there I came up with a name and began speaking to a few people about being on my board. There were a lot of people who thought I had lost my frigging marbles, you know?

Jason: So you post it on Facebook, basically hanging your shingle, right, that’s the modern way of hanging your shingle, and you put together a board. What services did you then focus on first? Where’s the point of entry so to speak?

Mark: Syringe exchange, bare bones street outreach doing syringe exchange and referrals to drug treatment, that was it. I had connections around the country, many of whose pictures are on the wall behind me, you can see Shiloh back there and Dan Big. These are people who had supplies and showed support from the start. Then the State having worked for those other organizations, when I made my announcement they said, “We’ll give you some supplies in exchange for data.” They couldn’t give me any money, but they could offer some supplies.

And so it began and at the time I was still working for the Blue Hill Civic Association, and I’ll never forget walking into that office when we moved to Albany Avenue, it was a new space, and it was the same space the Urban Leagues Community Health Program existed in previously, which was the program by which I gained access to a treatment center, which eventually led me to Willimantic. So it was kind of a full circle thing if you will, and I got to tell you, there was something spiritual about that room, about that office, about the moment where I knew something magical took place, something spiritual took place, and that it was the beginning of something.

Because of Dan we had access to Narcan, to Naloxone at the time, and because of Shiloh I was able to have a pallet of syringes dropped off as well as some other ancillary supplies, the safer smoking kits and what not. And then I had a background as a DJ, so I knew advertising and branding from that street approach and had access to inexpensive flyers, so I began branding everything.

Every single thing I wore had that brand. I put some small amount of money into label development, and from there everything had that brand and it was time to show up everywhere, make it known. So everything I wore had that logo on it, and I ate, slept, and drank it. It was day in, day out, week in, week out work, and for several years.

Then Naloxone became legal at the layperson level in Connecticut in October of ’20, but I already had it, and so it became legal but nobody had any including the people the state hired to do some of this stuff, like I was the one giving them supplies, I was the one who had it. And that was kind of resisted and resented, you know?

But from there I began doing trainings and hosting forums, town halls, and it was just one of those things where I implanted myself there to say, “This is what we do, this is how we do it, and we’re here and we’re not going anywhere.” And that mentality eventually just kind of caught on.

Then as people began to hear or and understand or learn about harm reduction, well guess who was that person to go to?

Jason: That’s a really impressive journey. So tell us about your street outreach teams, what’s a day in the life for them, how do those work?

Mark: This is where we will continue to lead because this is just essentially what we do. This is what separates us from the pack. I tell people my job description is very easy, it’s very simple, there’s I think four steps to my job description.

One, go out into the community. Find out what people need. Two, you provide what you do with those tools and services and meet those needs to the best of our ability. Then three, you show up again tomorrow and you do the same thing. And then the fourth and most important – don’t be an asshole.

You know, we exist because of them, we learn about services and service provision based on what they tell us, and they will tell us how we do that. So without them, there is no us. And oftentimes we may be the only person they encounter, especially my actively-using drug participants, in the course of the day we may be the only person they meet that does not have an agenda aside from what do you need and how can we help.

Jason: Powerful, that’s really powerful. How does it work in terms of where do you decide to go? You said you’ve got RV’s, five other vehicles with teams in each other them. What’s their mandate? They come to work in the morning, they grab the keys, they make sure the RV’s got gas in it, and then what happens?

Mark: Well it’s a lot more complex than that. The RV is a beast unto itself with a staff that exists solely in the field. They don’t come in unless we have a meeting or something. They have set hours, a set path if you will, and they go about their day.

I have a nurse on the RV with two other staff members, and they seek to meet folk where they are and provide what services they need. If that’s assistance with wound care with the nurse, or referral to medical providers, or syringe exchange. We also always have some type of snacks or something to drink to offer. And in addition to being able to connect people to on-demand treatment, we can also respond if for whatever reason a doctor’s office was shut down as a result of being found to be a pill mill, then we can show up on site at that doctor’s office and as people begin to show up for prescription refills we can engage them and send them from the office to our RV where we’ve got a set of medical providers who can begin to wean them down because oftentimes the prescriptions are way above what they would normally be in a safe level.

And for those who are on benzos [benzodiazpenes], you know, you can’t stop a heavy benzo script and have them go cold turkey, it could be dangerous. The same for opioids. So again, if there is a breakout or a rash of overdoses in any one area we can respond to that area to make sure we’re dispensing Naloxone, or doing drug testing of samples to find out what’s in the supply.

Jason: So you started getting Naloxone in 2014 and it was made available to the public in Connecticut in 2014, but like you said, it wasn’t widely available for quite a while, right?

Mark: At the time there were probably two to three types of Naloxone available. Intramuscular, a three piece which was a two milligram dose using three pieces of equipment you put together, and then an auto injector as well as nasal Narcan. The auto injector was about $2500 at the time, the three piece was maybe $70, the intramuscular was a $16 dose.

For that initial part, Connecticut did not go with the nasal because leadership knew their money wouldn’t go far because they didn’t have huge budgets for it, and the intramuscular would have been a hell of a lot more cost effective. And so arguing early on to have enough medication to make it sustainable cause why would you give out medication for a month, then run out of it and have to wait five months to get more when you can spend the same money and have medication to give out through that whole time period.

So we’ve always been very blessed to have access to Naloxone from the very onset, and we’ve had the longest continuous running overdose prevention trainings, and just made sure people had access to this life saving drug. And why wouldn’t we? It has no side effects. It has no side effects. The only side effects to Naloxone is that it saves lives.

Jason: Yep, we talk about that with people a lot that the side effects from CPR are catastrophic, if not sometimes fatal, we talk about mis-administration of epinephrine, like an epi autoinjector, which has possibly catastrophic side effects if not fatal. But with Naloxone or Narcan, you can pump someone full of that all day long and nothing’s going to happen to them.

So you and I we first met back in 2018 or 2019 and we were trying to get these programs started for opioid overdose response networks. And the whole premise was that there are a ton of people walking around with Naloxone in their pocket, but they’ve got no idea when there’s an overdose, and so we went around and talked to hundreds of potential partners to find out if they would like to work with us on a program where, when an opioid overdose is reported to 9-1-1, an alert is sent out to community responders with lived experience who carry Naloxone to alert them where the overdose is, allowing them to possibly get there before 9-1-1. Because as you’re well aware, one of the things about opioid overdoses is that seconds really count. Just like in cardiac arrest, if the heart isn’t pumping, no oxygen is getting to the heart and therefore the heart is dying. And the same thing in an opioid overdose: If someone isn’t breathing, then oxygen is not getting to their brain and they’re suffering brain damage. The longer they’re not breathing, or they’re not breathing adequately – because as you know in many opioid overdoses they’re breathing but the respirations are shallow, there’s not adequate perfusion.

So just like with cardiac arrest, in opioid overdoses, seconds count. So we were saying look, if you can get people there quicker than 9-1-1, then that’s going to help outcomes. But we had a lot of trouble getting people to start this program with us until we met you. And I remember the first conversation we had, you said, “this is a no-brainer”. And we got started and I wish everybody we talked to after that had the same thing, but it hasn’t happened that way.

But you’ve now been running this program for about close to three years I think. I remember exactly when it started was I went to Hartford to give the final training to the responders and the whole time I was there – this was March of 2020 – I remember the week before that I was so spooked because we were watching the news with this Covid thing. And I was like, “oh no, we’re going to get cancelled.” And thinking if we don’t get this program up and running, and this turns out to be a really bad pandemic, it’ll be years before this program gets started. And I remember calling you up and being like really nervous asking if we were still on for training, and you said. “Absolutely”. So I raced up there, gave the training, I got back in the car and I was driving back to my brother’s house and I turned on the radio and there’s Governor Lamont saying, “We’re going on lockdown.” And I remember thinking, “Wow, well we’ve done our part, if they don’t launch the program, totally understood, but fingers crossed.” And then in the first month you responded to 60 overdoses.

So tell us about this program, how does this work? What does it take, who is involved, how does it work?

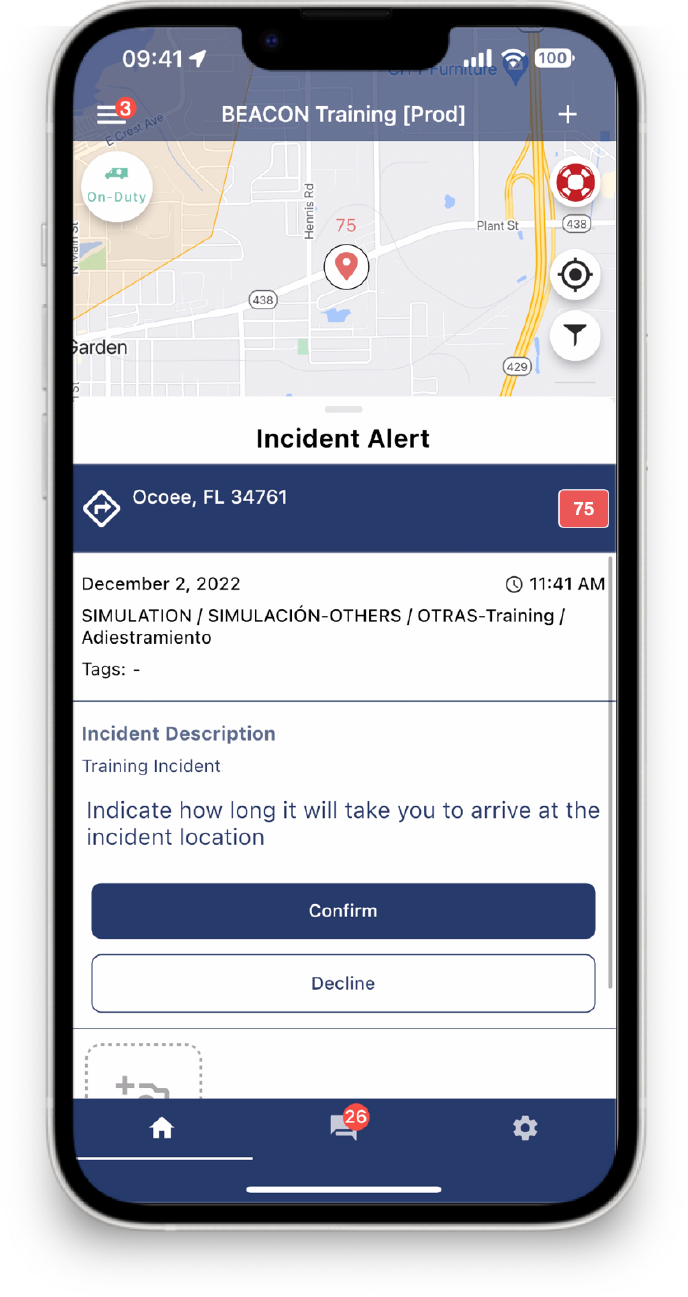

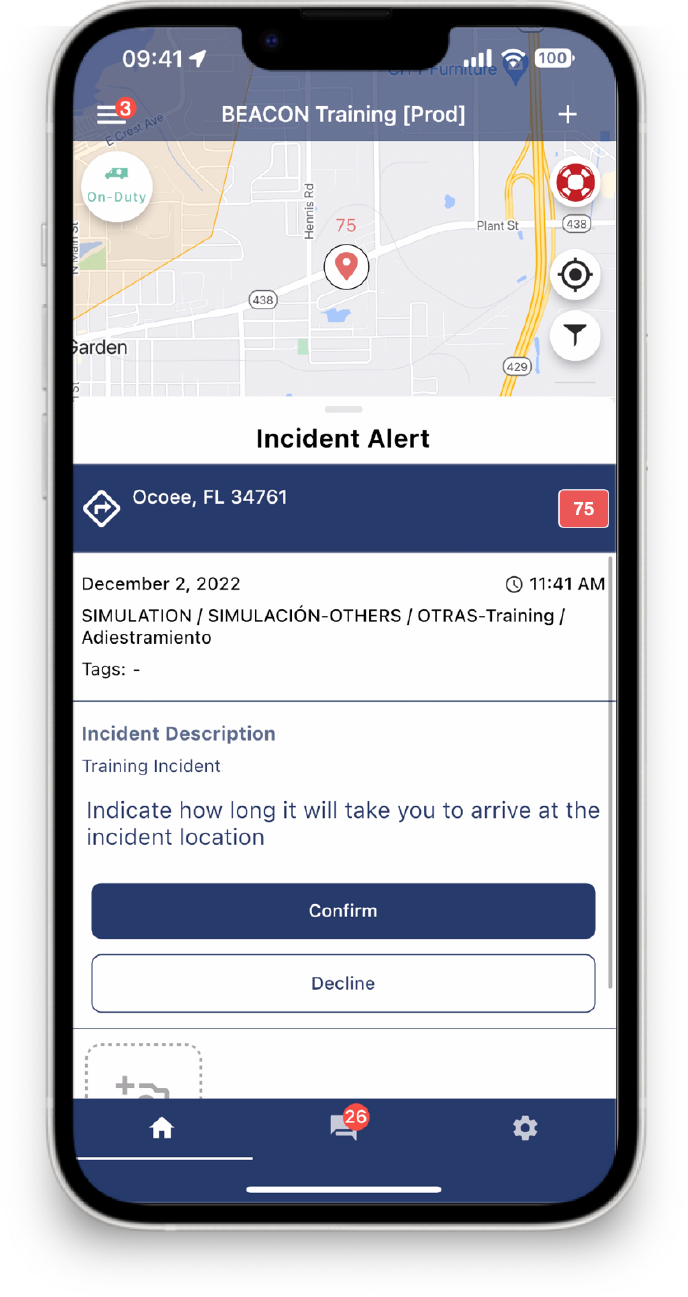

Mark: It doesn’t take a lot at all to run the program. It’s all text [message] based so you don’t have to have any special equipment, save for a telephone that can receive text messages.

There were three ways off the bat we let people know about the program. First off we printed some bands that said “Don’t run, call 9-1-1” or “Call this number” which would let us call 9-1-1 for them. We knew that 80% of overdoses happened in the presence of someone else. Those people are the true first responders. And how do they respond? Well, we figured out and we knew from our polls and from speaking to people, the number one reason people did not call to report the overdose was fear. Fear of police, fear that they didn’t know their rights, they didn’t know about Good Samaritan laws. And so we were able to inform them and tell them if you are scared call us, you can call us and let us call.

Then anytime someone sees one of our vehicles and the flags on them they’d flag me down and we knew what it meant. We then also had people sitting around listening to 9-1-1 to listen to the emergency responders scanner. And if they heard something they just had to key in the information to the best of their ability and the Beacon would then shoot a text to the responders out in the street.

Join the thousands of responders using Beacon worldwide.

Jason: So the text goes out, people respond, they arrive on scene. Sometimes they get there before police, fire, EMS, sometimes they don’t. How does that work? Because some people would ask why you are going when 9-1-1 is already on the way. What happens if you get there and 9-1-1 is already on scene?

Mark: Oftentimes when people come back from an OD they are confused, you know, depending on the environment and the individuals, they won’t be very forthcoming to answering questions. And quite often the people are known to us, so we’re able to assist and say how can we help.

And you know what happened as a result of us showing up to so many sites, at first EMS and fire sometimes had an attitude like, “Who the hell are these people? How do they keep showing up at sites and why?” But they eventually learned who we were and that this is what we do and that led to conversations and we developed a network which became our task force and we built a really good rapport between ourselves, Fire, and EMS.

Now once the city at large came into that fold, it took a different direction, we’re still a part of it, but it’s not the same as when we began to get together and talk about how can we collaborate how can we further make sure that we can save lives, you know?

And I introduced them to the Beacon system because they couldn’t understand how we could respond to scenes quicker than them even though they are flying with their sirens and everything else. And I’m saying it’s because we have people who are in the field at any given time, you know, 12 to 14 hours a day, so it’s often a lot easier for us to move because we are already out there.

Jason: To play devil’s advocate here, because I get these questions all the time and I’m sure people listening will have the same questions, and I’d just love for you to answer them because you can better than I can. The number one question we hear about when we propose this program is, “What about the safety of these responders?” Right? What I remember one person said to me, someone with a public safety background said, “You are sending people with good intention into harm’s way. These are dangerous scenes, and they should only be responded to by trained law enforcement professionals, and if you’re going there as EMS, you should only go with law enforcement there on the scene with you.” How would you respond to that?

Mark: Bullshit. You know, in not so many words, ludicrous. Unproven.

Jason: Well, so what they’ll say is when you have resuscitated someone who had just been overdosing and on death’s door, that they become violent and aggressive and will start attacking people.

Mark: Well again, bullshit. In all my years I’ve lost count of how many overdoses I’ve reversed, but it’s hundreds and hundreds that me and my team respond to and we’ve never had someone get violent.

And the one thing I’ll say again that separates us from the pack is the face that our services are non-judgmental. There’s a level of care that goes along with our work, so people know our intentions. I will say, when law enforcement is present, people are agitated. You come to, unaware maybe what happened, now you’ve got police, you’ve got all these people around you asking questions, and some of them quite frankly can be assholes. So then one response deserves another, and I’m sure some negative things have happened, but for the most part again, a lot of other people just repeat shit they heard from others. You know, I know people who’ve never reversed an overdose but they’ll say, “Be careful because when they come back they’ll be volatile, they’ll be angry, they could be violent.” And it’s like, “F*** you, um, have you ever reversed an overdose?” Stop repeating things you’ve heard because it’s hard once negative information has been perceived from trusted sources it’s taken as fact when really it’s false information.

Jason: So on that note, can you please respond to these videos that are going around of a police officer touching fentanyl and immediately keeling over. What’s that about?

Mark: Bullshit. Look I tell people don’t take it from the large black guy, you don’t have to. There are medical professionals from Harvard to Yale to Istanbul that will say it is medically impossible to overdose from touching that product just like that.

Now listen, I’ve got bags upon bags upon bags of fentanyl. All product. Purple, white, brown, and you know I handle the bags. For some trainings I will rub my hand – I don’t ask anybody else to do it – but just to prove the point that it’s misinformation from trusted sources I’ll rub my hands on them.

Here’s the deal. Information from the prestigious medical institutions like the CDC, the National Drug Policy Council, Office of the President, you know, all of these places have said you can’t OD from touching it.

Jason: So fentanyl is obviously a huge problem. How do you think that we are going to solve this or at least tamp it down?

Mark: The only way to truly get these deaths down would be to get more heroin immediately back into the market, or a product that is more pharmaceutical based. What makes Fentanyl so dangerous is the way it binds to itself and the various analogs that are coming out. Combined with the market, it’s a marketable product right now. There’s money to be made by everybody and it’s so marketable that it’s not going away. Heroin on the other side is a more stable product.

People are going to use regardless. People have been using drugs since the beginning of time, since early times people have found ways to alter their state of mind.

Things are going to get worse, I don’t think we’ve entered the fourth wave of this epidemic, because we haven’t had counterfeit pills. Listen, the United States makes up 5% of the world’s population, yet we consume upward of 80% of the world’s prescription drugs. What that is is a market. It’s an insatiable, multi-billion dollar market.

And if you can take a $5,000 investment, buy a pill press and flip that investment into a million dollar return, are you kidding me? We’re a capitalistic society where the first rule of business is market. And if we couldn’t stop bootleg Nikes or bootleg CDs or bootleg purses, how do you think we’re going to stop bootleg Percocet?

So we’re in for it. Will some things help? Yes. Saturating towns with Naloxone and reaching that saturation point, it will help. Removing the stigma of helping people address overdose and responding to overdoses will help.

Jason: So you’re advocating for decriminalization or legalization. Better to manage it and regulate it than leave it to the black market? Certainly a strong case for that because traditional ways haven’t worked so well.

Mark: The most effective public health responses are not favorable. They’re seen as enabling.

Jason: That leads me to my next question. We talk to people about an overdose response program, we talk about getting programs so that community responders can guide people to medicated assisted treatment. A lot of the pushback that you hear is, “You’re enablers.” How do you respond to that? And I’m just going to play Devil’s Advocate again here, when I was working on an ambulance, I would hear this from coworkers who would say, “We reversed the overdose today so that they could overdose again tomorrow.” How would you respond to that?

Mark: Reverse it again tomorrow.

You know, substance use disorder from opioids, once they experience that, oftentimes you’re not using to get high, they’re using to keep from being sick. The addiction creates a paralyzing negative effect of not having that drug. And treatment may not be an option because of insurance, it may be that they’ve had issues, it may be they are just scared of the withdrawal that they’ve experienced in the past. There are a number of reasons or barriers we have to figure out how to really work with people and reduce those barriers or find ways to keep them safer, which is really what harm reduction essentially is.

Join the thousands of responders using Beacon worldwide.

But the bottom line is, we have to continue to do it. We have to do it until something catches or else, you know, we’re going to lose more and more people.

Jason: Absolutely. Lot of truth to that. What’s your immediate goals, what are you hoping to achieve in the near future?

Mark: A Community Center. One of the negative effects of Covid that hit the urban center was the closure of churches and spaces that hosted 12-Step fellowship meetings. It’s also created bigger food deserts, many places that provide evening meals and things of that nature are no longer available.

So I want to begin to connect people. If the opposite of addiction is connection, Covid separated us even further. We have to begin to connect people again. So a community center would help us do that.

Jason: That’s awesome work. So for anyone who’s looking to get involved, I mean, you’re truly a community response organization because you are responding to the community’s needs. For other people who are looking to do the same, can you give some high level kind of principles that have worked for you throughout the years?

Mark: Stay true to your work, you know, if you believe in it. Always seek to better. Better your products, better the presentation, whatever you know, the communication, education, information.

And repetition. It doesn’t always happen the first, second, or third time. You have to keep plugging. You have to keep plugging. I hit roadblocks every day, it’s what has shaped my work is how I’ve learned to sidestep and respond to those roadblocks which has led to the level of success we now have.

Jason: Excellent advice. And I can tell you personally, many times I’ve asked myself you know, is this all working? Is it worth it? And I’ll tell you the one thing that keeps me going is I believe that this works. Like you said, I believe in what we’re doing. I can’t imagine doing something that I didn’t believe in — I wouldn’t want to do that. That kind of conviction, almost maniacal conviction, it’s going to take you a long way.

Well Mark I thank you so much for your time as always, it’s a genuine pleasure, this has been really informative.

Mark: Alright, I appreciate it.

Jason: Absolutely, we will be in touch, take care.